Choosing the music for a concert is at best a somewhat mysterious process (please see my earlier post for concert details). At the end, we hope that the audience will feel that the music fits together, that there is a flow and a connection among the pieces that makes the progression of pieces almost inevitable.

In the case of this program, we began with the Pinkham Christmas Cantata. It’s a great combination of challenging and moving moments for both audience and singers, and gave us the opportunity to design a program where brass played an important part—a treat for the Lyric Chorus, best known for its partnership with the fine pipe organ at San Francisco’s venerable Trinity Episcopal Church.

The Pinkham was designed to be sung with two brass choirs, or one brass group and organ (the version we’re doing). As we thought of what to program with it, Gabrieli’s In Ecclesiis came to mind. Just as the Pinkham is a 20th century tour de force, the Gabrieli occupies much the same position in the early 17th century. It’s actually written for a slightly larger band of instruments, but was pretty easy to arrange for our current instruments.

Since we were doing In Ecclesiis, why not include another Gabrieli, or some other multi-choir music? In short order we had added Gabrieli’s Hodie Christus natus est and Schütz’s Jauchzet dem Herren. Even though it doesn’t use brass, pairing a Schütz setting of Hodie made good sense, giving us both the opportunity to hear the text from a different vantage point as well as simply enjoy more than one work by this marvelous composer.

But wait: there’s still more music with brass! The Dufay Gloria ad modum tubae, the earliest work on our program, uses both choral and instrumental forces very sparingly, serving as a bridge from earlier chant and monophonic pieces to the later polyphonic works of the Renaissance. Because of its simplicity and directness, this work seemed like a great way to begin the concert. The Schütz Hodie, mentioned earlier, followed easily, even though the two works were separated by a couple hundred years, with the one work leading into the splendor of Renaissance polyphony, and the other a simplification of the complexity that often resulted from that polyphony.

As long as we were using brass, it made sense to have at least one work that featured our fine instrumentalists: one of Gabrieli’s Canzone per Sonare, a song without words. Although it fits chronologically between Dufay and Schütz, it follows these two in our program as it moves from the simple to multi-voice and multi-choir pieces.

After the multi-choir pieces by Gabrieli and Schütz mentioned earlier, we wanted a change of pace, both for contrast of textures and, quite frankly, to give our instrumentalists a break. Since our concert is in December, most of our music has either a Christmas or holiday theme. With that in mind, I couldn’t resist Joaquin Nin-Culmell’s delightful La virgin lava pañales. I studied composition with Don Joaquin, and came to appreciate his blend of the contemporary with the traditional. Our set of Hispanic pieces grew from that beginning, with the Vasquez En la fuente del rosel coming from a set of early Spanish choral music that Nin-Culmell edited and the González Serenissima una nocheshowing that the distance between classical and folk traditions is not very great. There is also an element of anticipation in this set, as we look towards our spring concert, Voices of Immigration¸ built around family and individual stories of our chorus members.

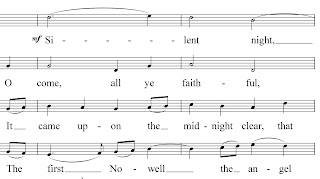

We wanted to end the concert with audience participation, and decided to bring back the Christmas Fantasy we premiered in 2009 (the composer part of me was quite pleased, since others suggested that we repeat the work!). In earlier planning, the second half of the concert consisted of the Pinkham cantata and the fantasy. It became apparent that something more was needed (in the Lyric Chorus we’re always looking for just one more thing!). I decided to add the brass quartet to the organ accompaniment—I can’t wait to hear it. In addition, as I was looking for that one more thing, I came across Victoria’s O Magnum Mysterium Mass, very strongly modeled on his moving O Magnum Mysterium, and our concert was complete.

There are layers of connections among the pieces on this program. The predominant language is Latin, and yet as early as Schütz we have a work in the vernacular (German, in this case). Our first half ends in Spanish, yet a Spanish composer (Victoria) brings us back to Latin at the start of the second half. There is a bit of a chronological ordering, with the oldest piece first and the newest piece last, and yet the flow of musical texture and style was much more important to us than the work’s provenance.

As we move into our closing weeks of the season, with an increasing sense of urgency as we realize that rehearsal time grows ever shorter and our list of spots still not fully learned grows every longer, we nonetheless revel in the richness and variety of the music, and look forward to sharing our passion for this music with our audience.